CASABLANCA Courts NBA and LA Swagger

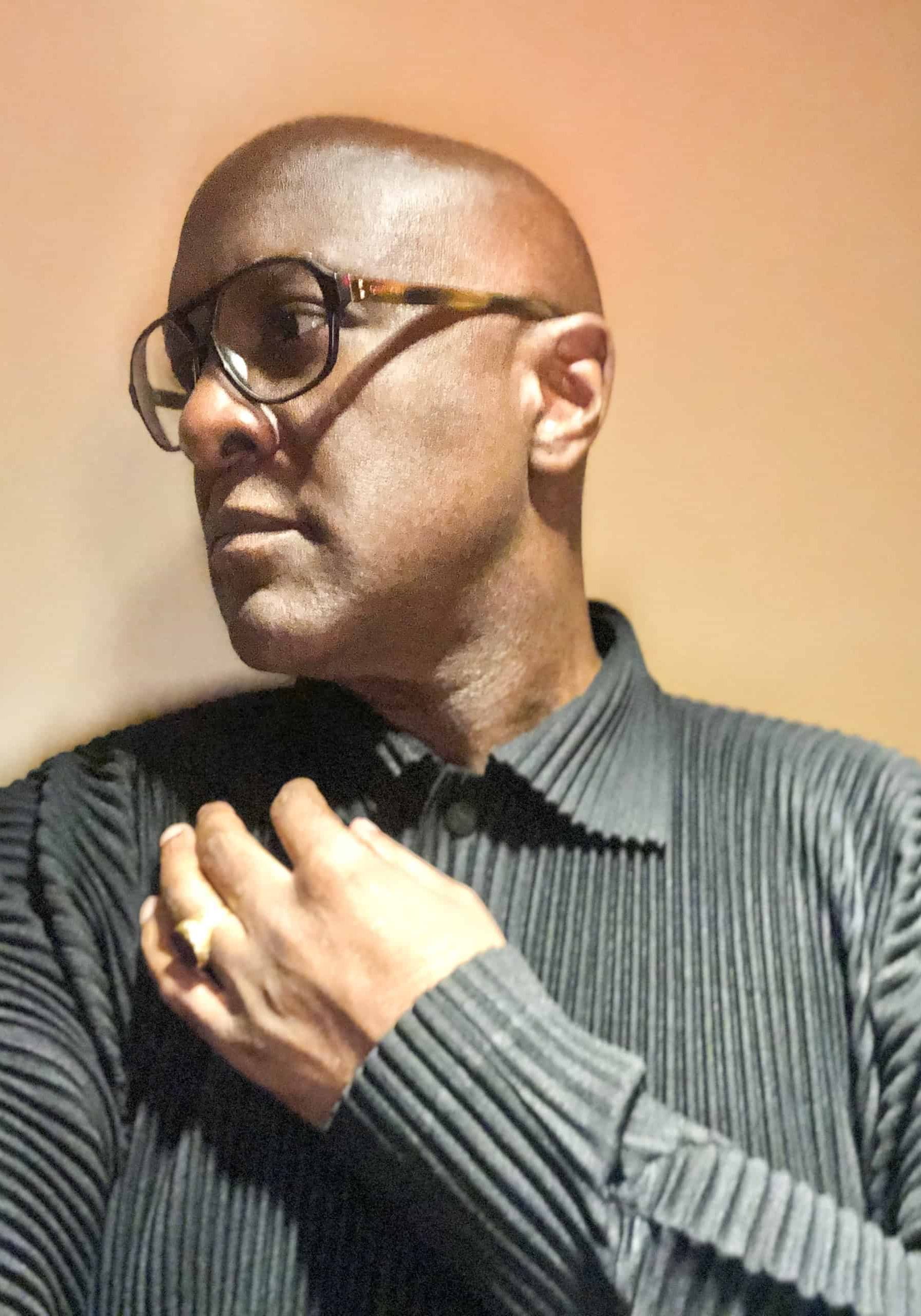

Patrick Michael Hughes Fashion Editor Men’s Fashion Writer

From Boston to New York Milwaukee to Oklahoma City or Denver to Minnesota with a classic ‘ally-oop’ to Los Angeles. Basketball stars are more than just champions on the court—they’ve long been cultural and fashion icons. For over five decades, the media has followed their off-court style with as much intensity as their on-court prowess.

Think back to the days of Knicks’ legend Walt “Clyde” Frazier. Whose Super Fly echoed urban cultural shifts from the late ’60s into the early ’70s. Then there’s the slicked-back, power-suited look of Pat Riley coaching the Lakers in the ’80s. An image that was reflective of success and a winning record. And who could forget Dennis Rodman, whose boundary-breaking wardrobe in the ’90s foreshadowed the gender-fluid fashion revolution?

Fast forward to today, and NBA tunnel swagger has become the modern-day runway. With players’ personal styles ranging from elevated casual—baggy pants, tank tops, and loose-fitting zip-ups. To avant-garde ensembles that push the limits of high fashion. Social media has only amplified this synergy between basketball and fashion. Making every arrival at the arena a moment for sartorial expression.

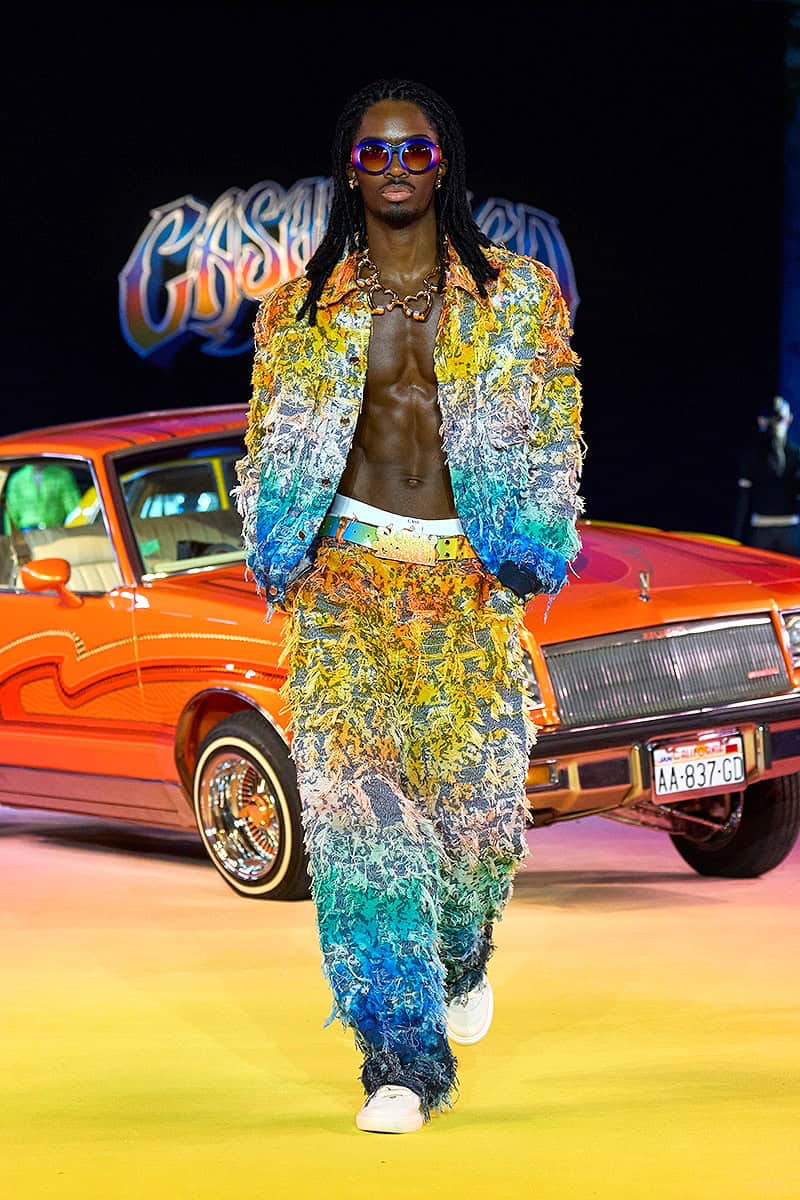

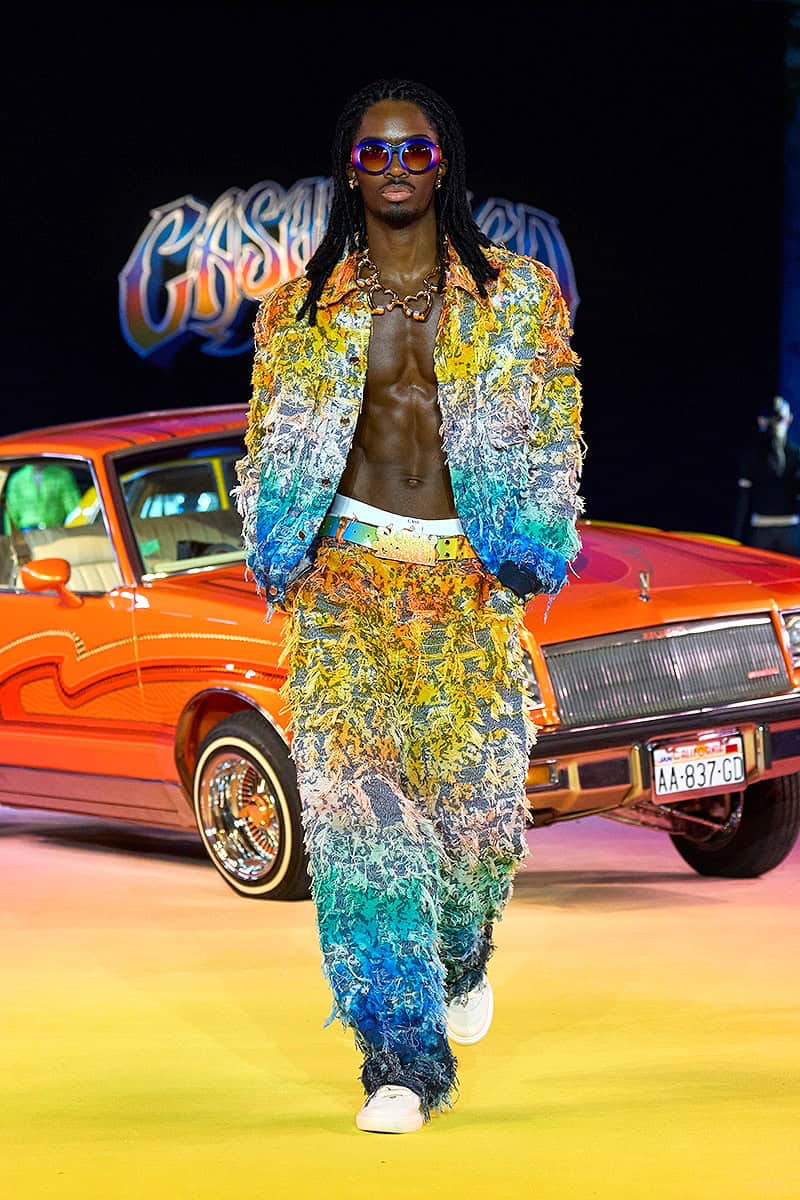

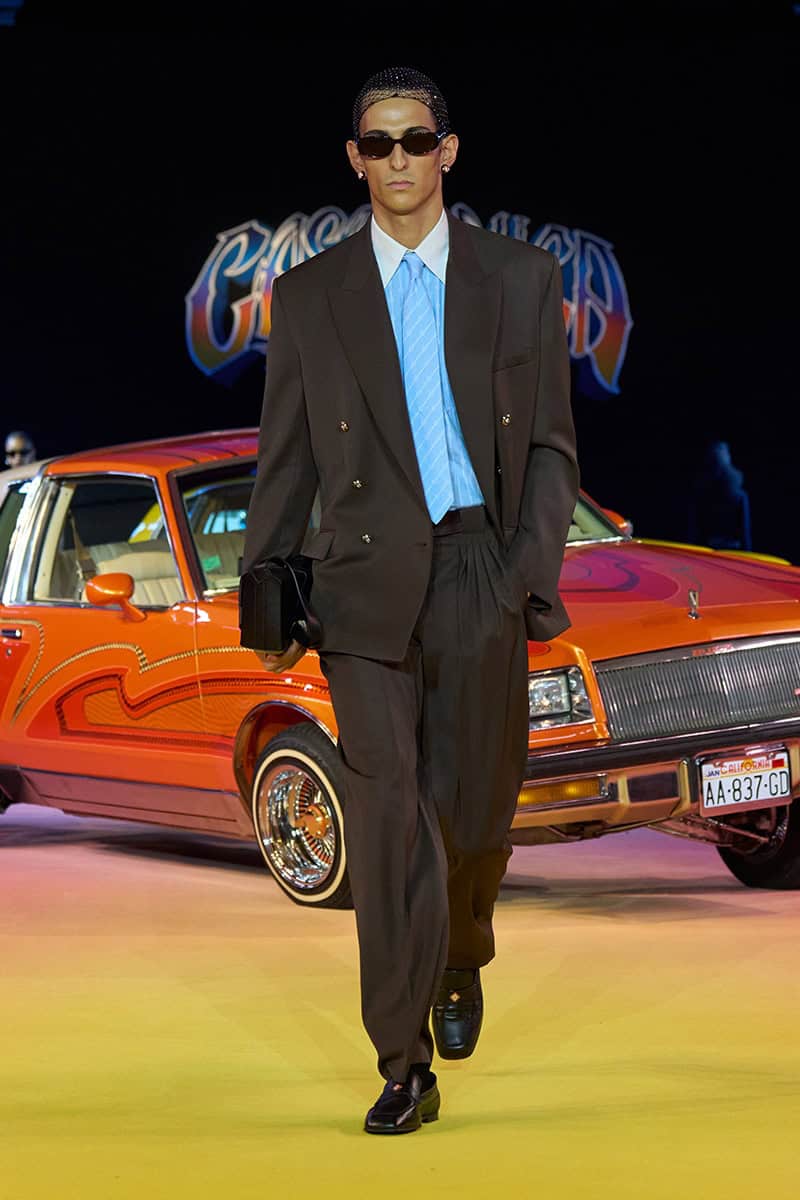

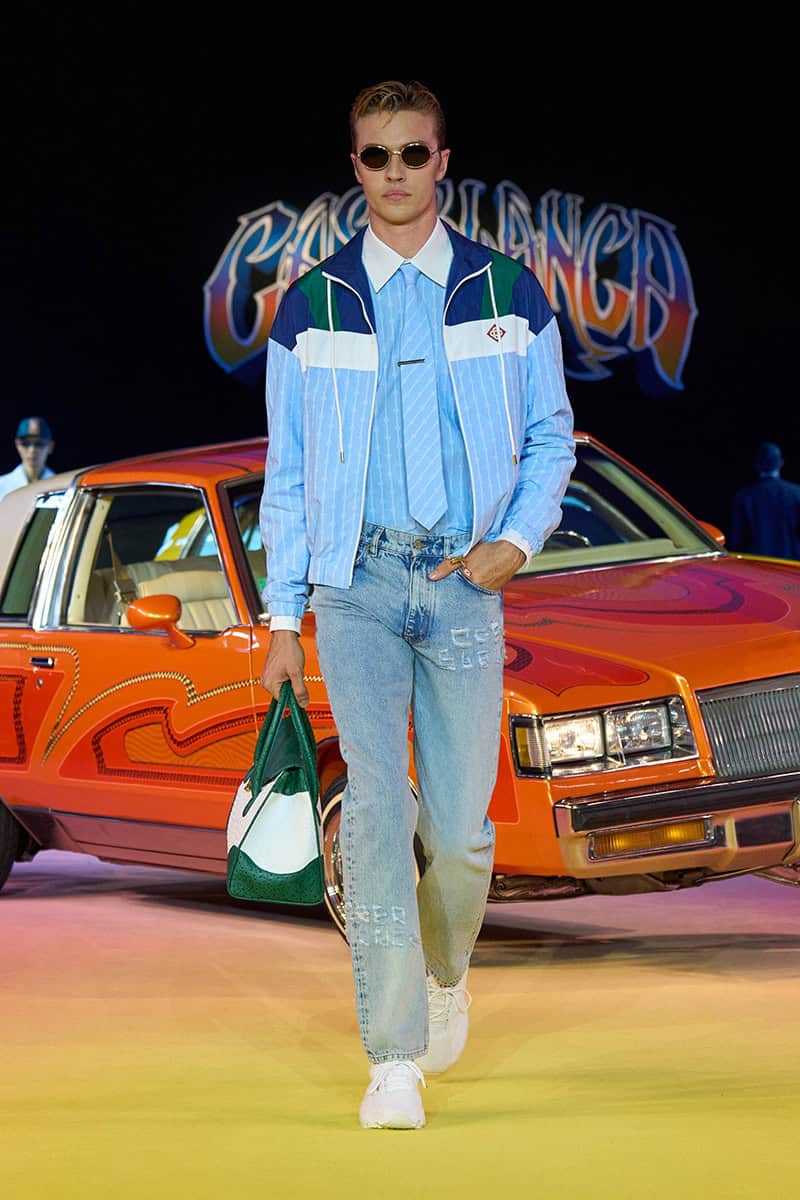

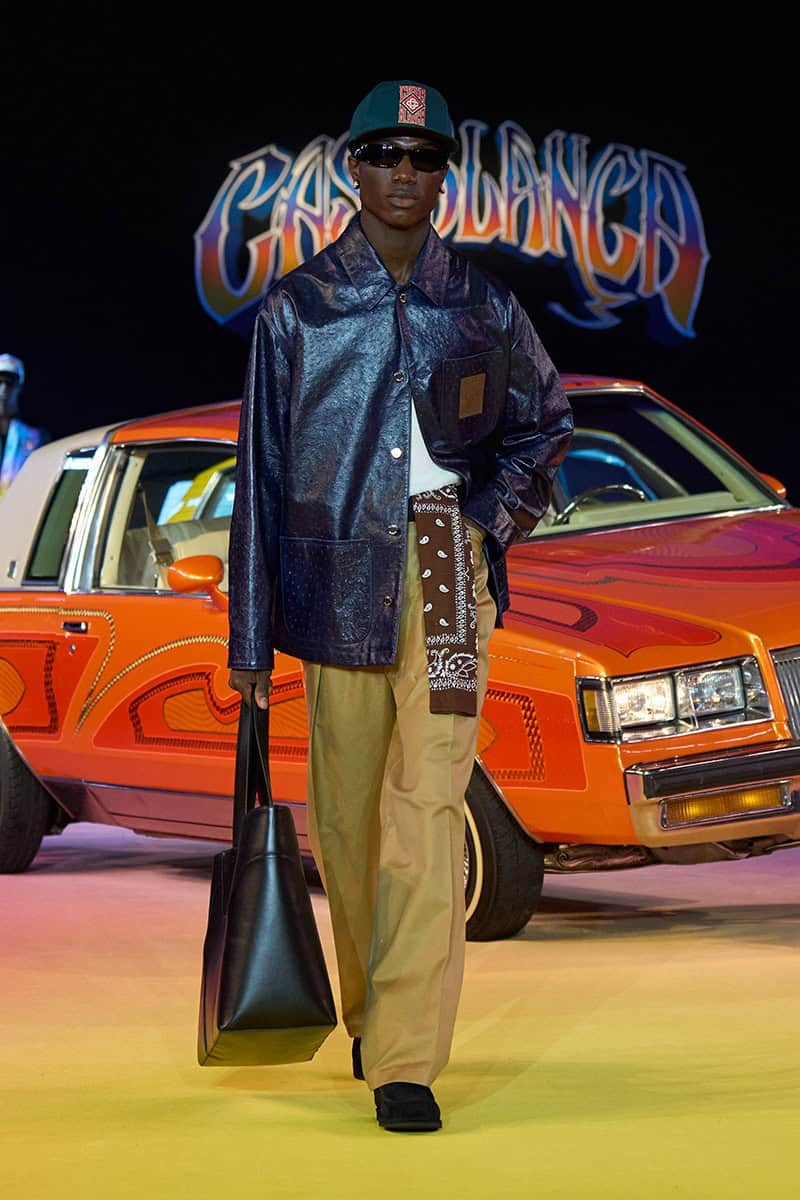

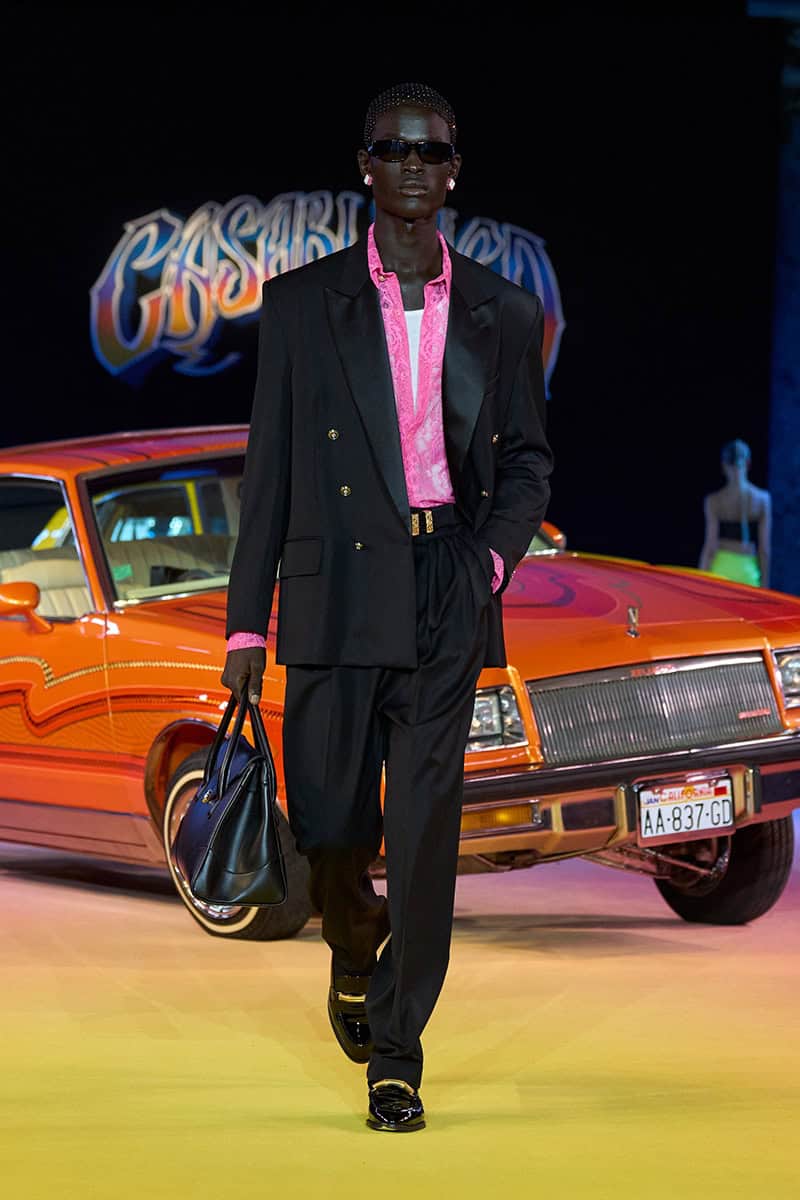

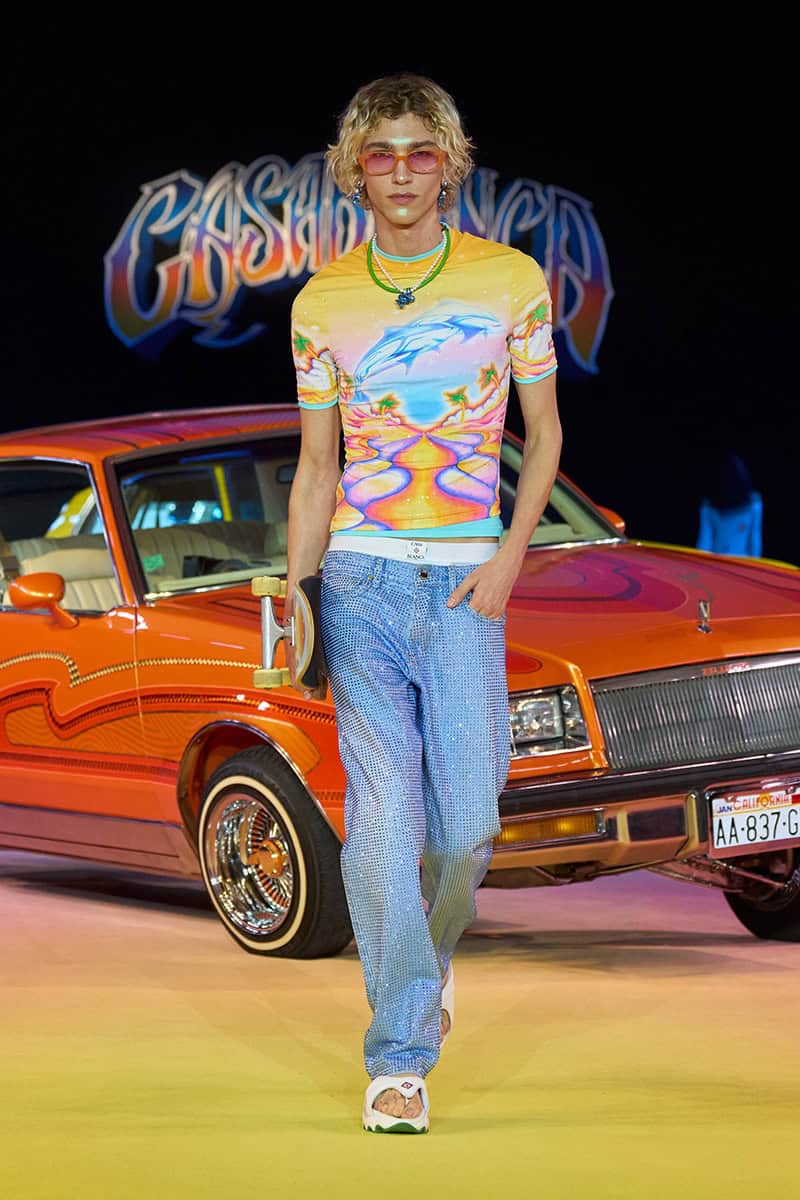

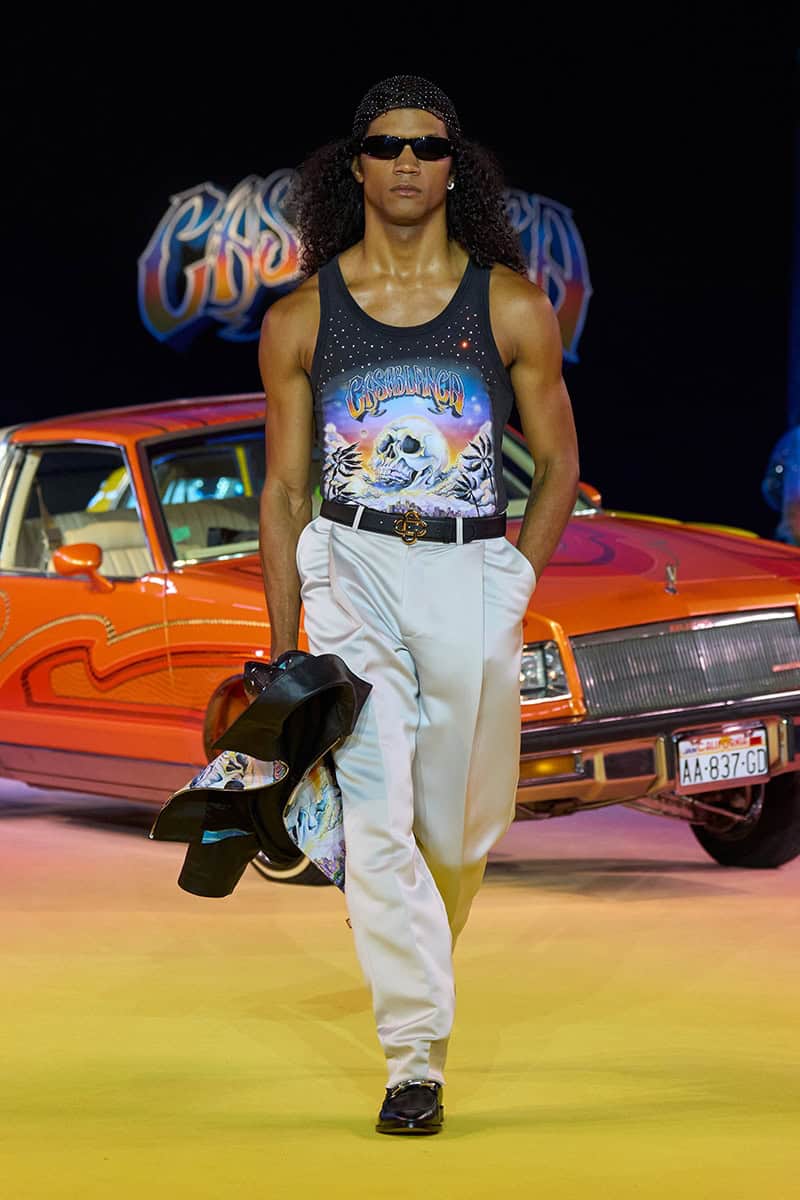

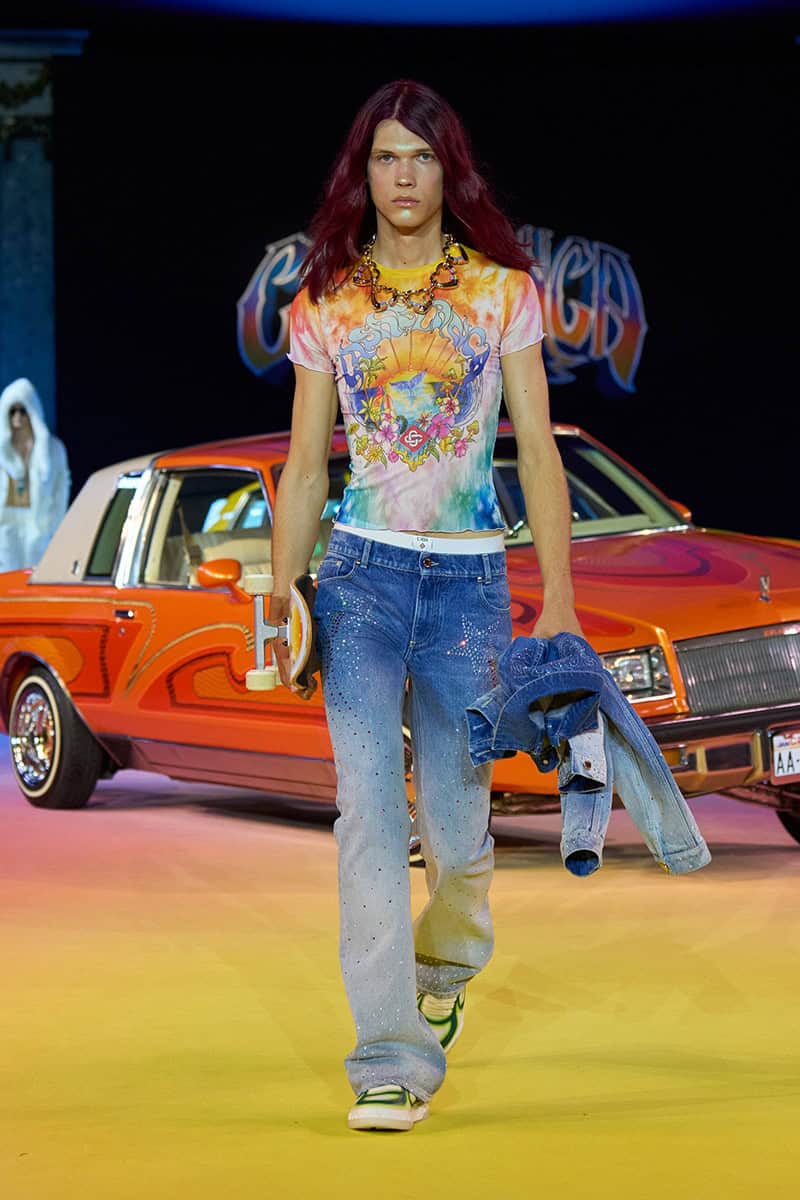

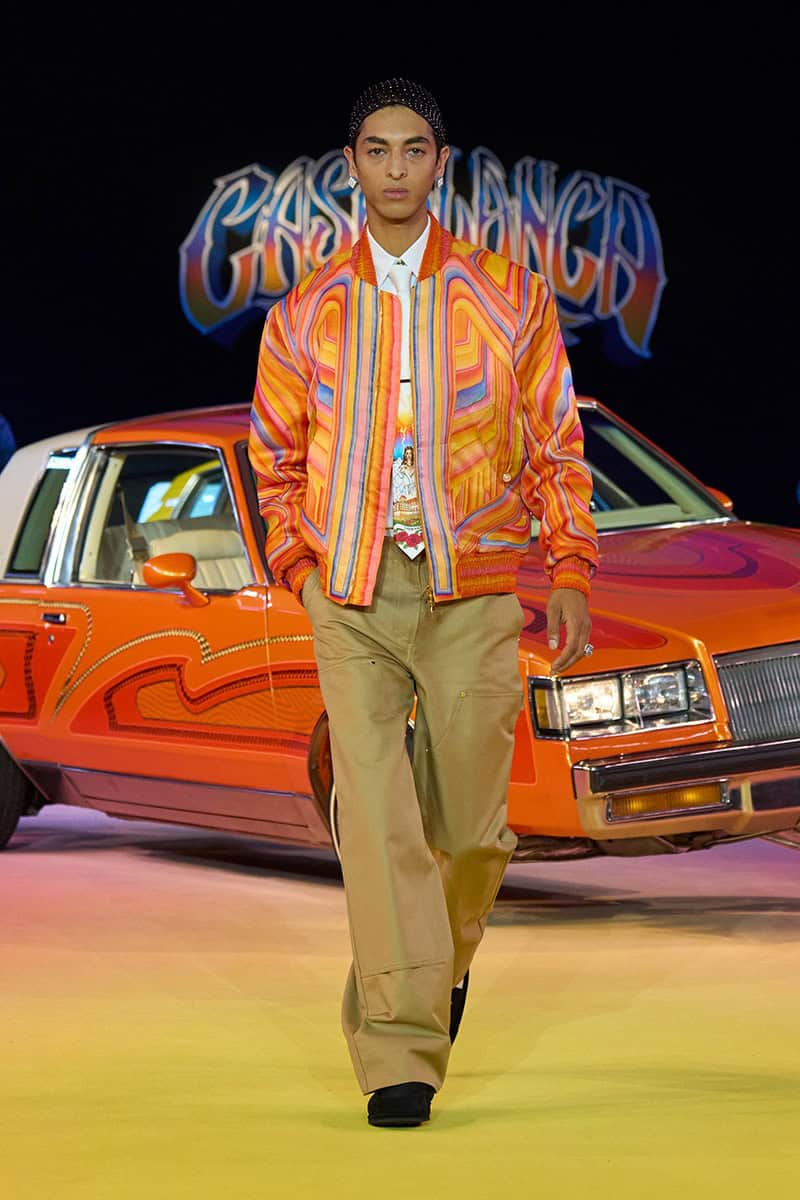

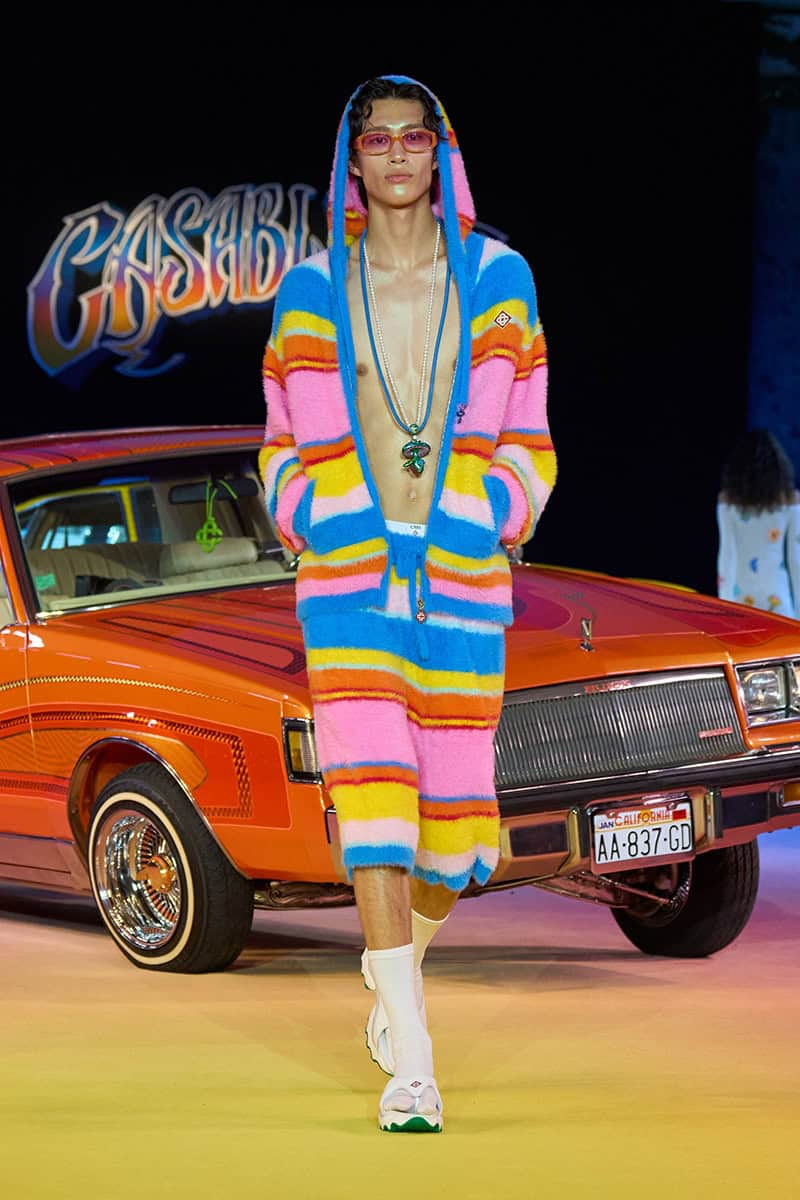

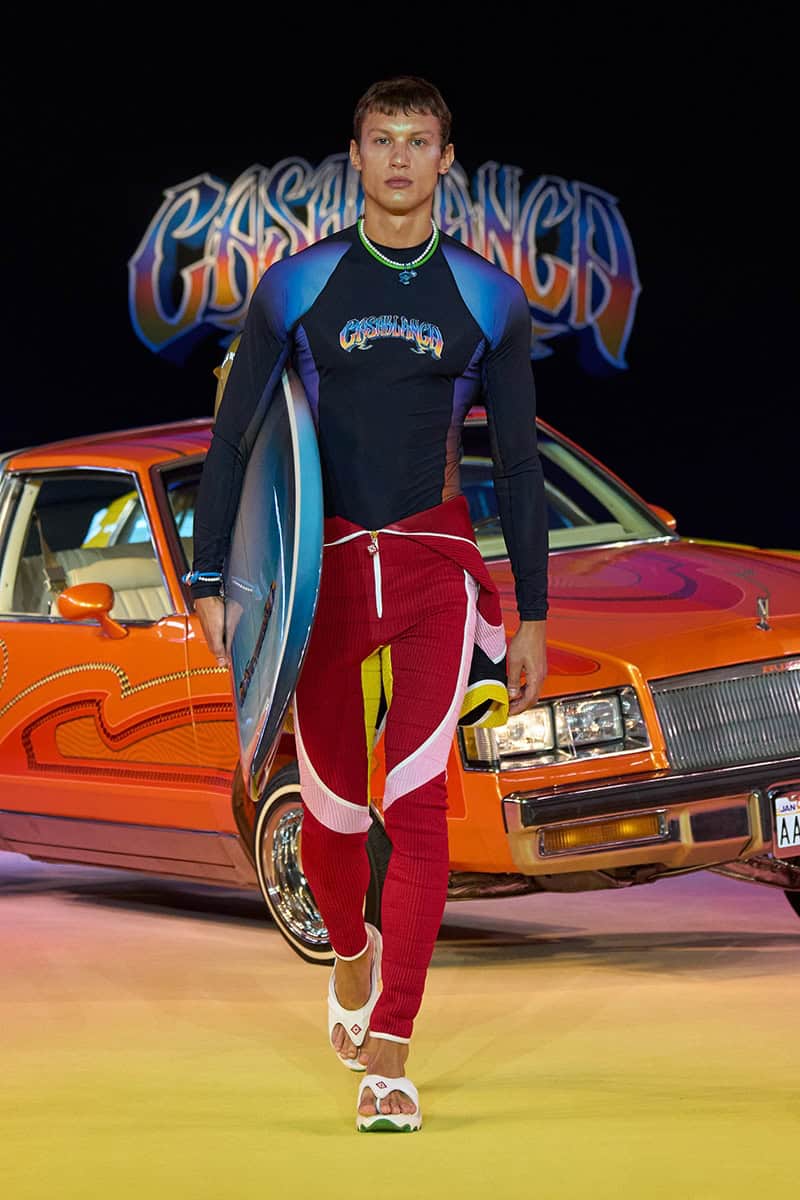

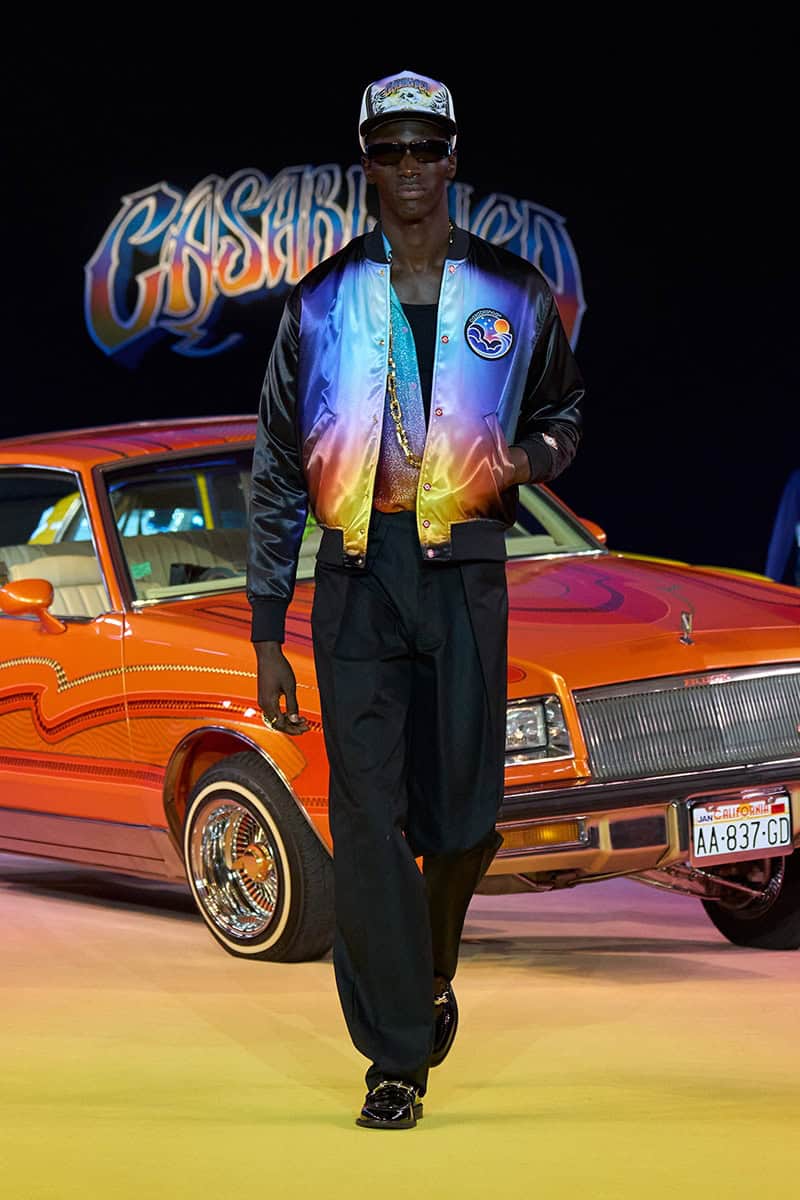

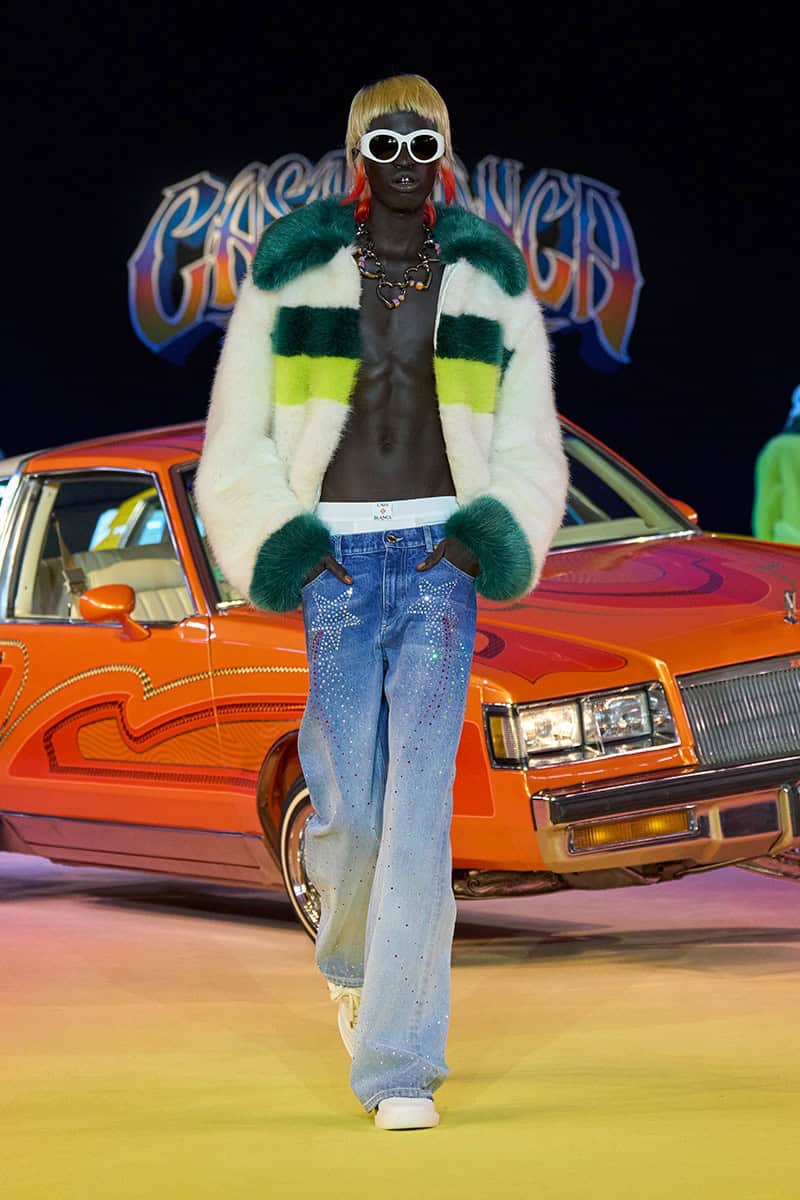

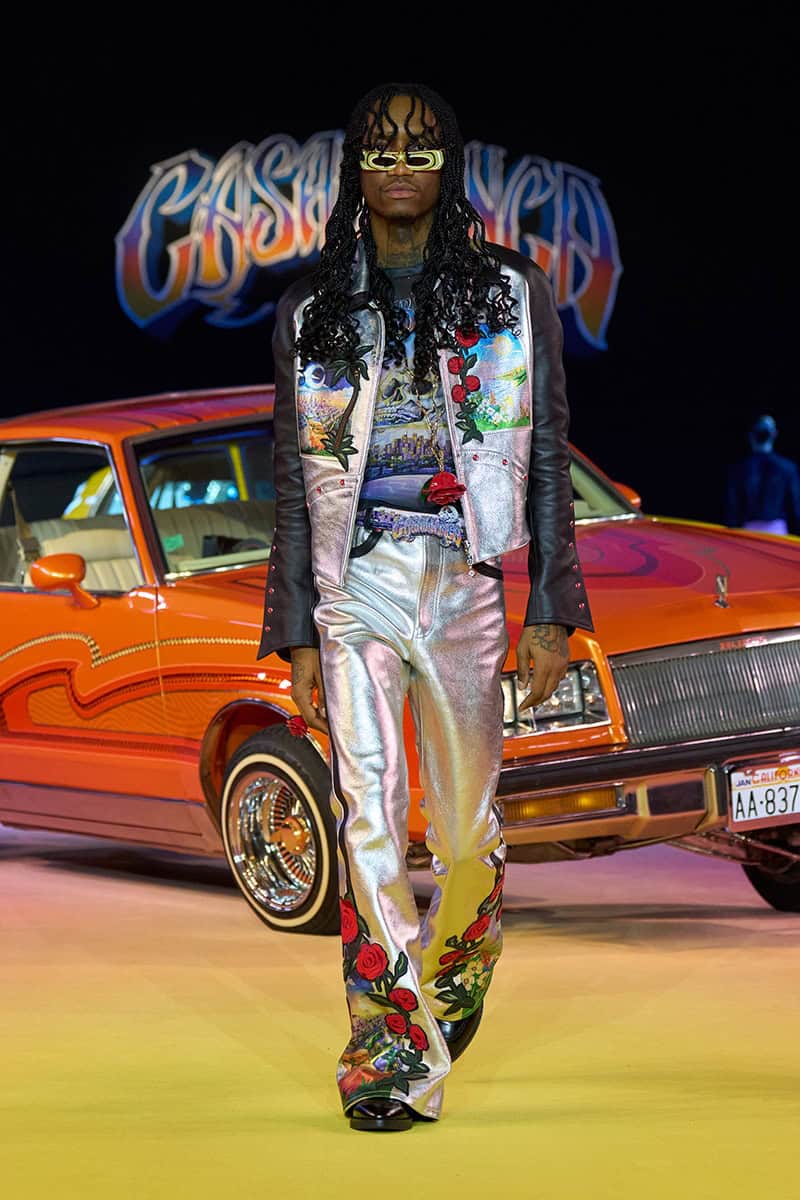

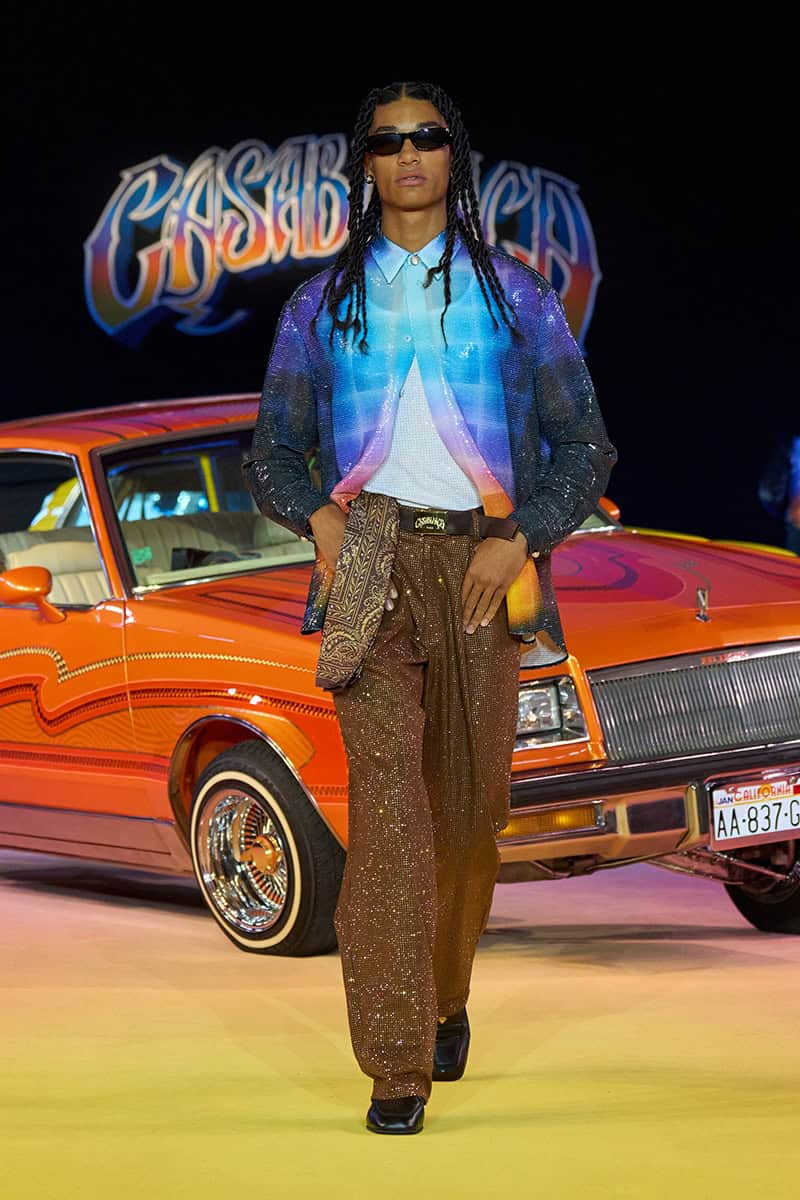

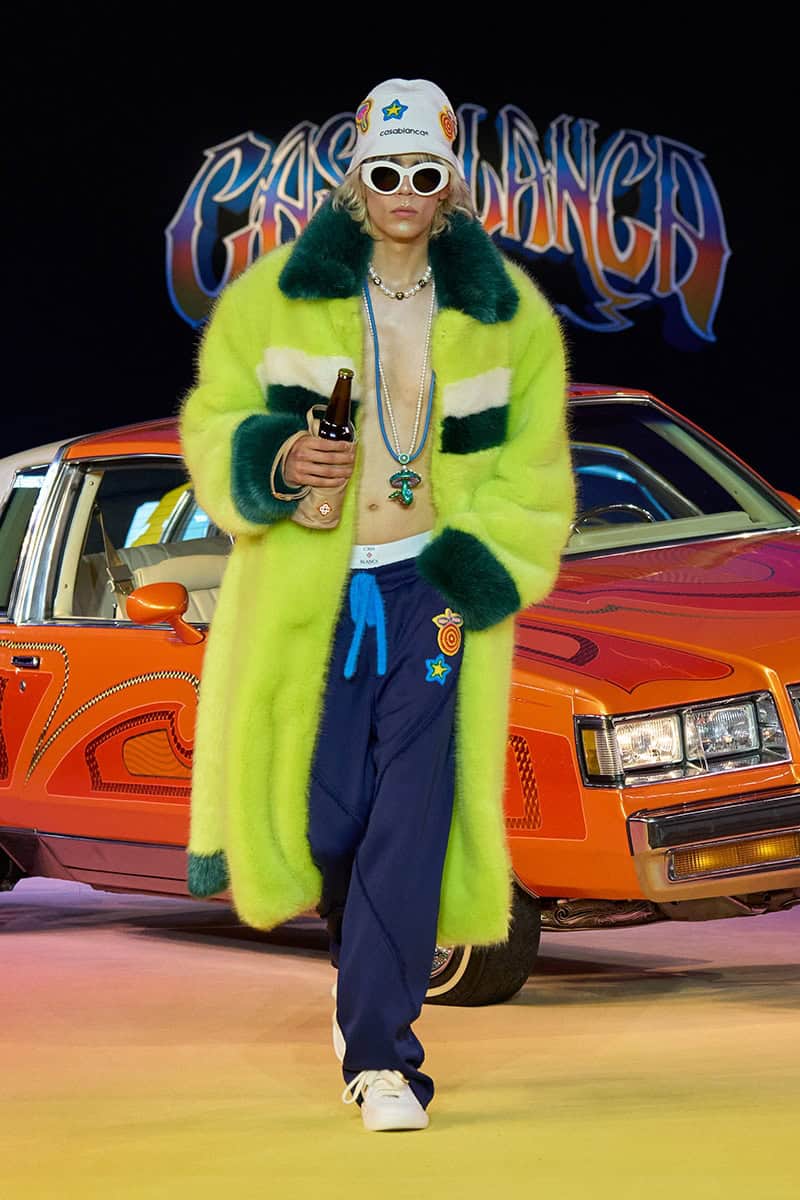

At Paris Fashion Week, CASABLANCA’s Creative Director Charaf Tajer tapped into this rich legacy. Blending Los Angeles’ iconic sports style with Mexican-American counterculture. Models strutted around Lowrider cars on a vibrant yellow runway, each look brimming with character and purpose. The collection was more than a tribute. It was a statement on the enduring relationship between sports, culture, fashion and a storied American city..

Parallel to sports culture, Tajer Spring 2025 collection for CASABLANCA delved into a kinship. With Mexican-American heritage, particularly the Lowrider community in Los Angeles. For Tajer, a Moroccan-French designer with roots in the working-class, the connection was personal, a reflection of his own upbringing. When designers mine cultural narratives, the results can range from compelling to disastrous. In this case, it was a delicate homage.

Historically, it’s worth noting that the baggy aesthetic now ever present in West Coast fashion. Was first popularized by Mexican-American youth associated with street gangs in Southern California. From the high-waisted zoot suits worn by Pachucos in the ’30s and ’40s. To the buttoned-down shirt, tie, and denim or leather jacket look, Chicano style has long influenced mainstream fashion. Over the years, this cultural symbolism has often been appropriated by high fashion without proper recognition of its roots. From emerging labels to luxury houses, fashion has frequently borrowed from subcultures born out of social oppression. Chicano motifs, in particular, have been commodified on racks and runways, with little acknowledgment of their origins. Tajer’s collection, however, offers a more respectful nod to this community. Highlighting the power of representation when done with sensitivity and an understanding of cultural depth.

One of the most striking elements of CASABLANCA’s collection was the airbrushed t-shirts. Unmistakably drawing from the Lowrider culture of Mexican-American Los Angeles. These weren’t just fashion statements; they referenced a rich history. Where young Mexican-Americans took castoff cars—the only ones they could afford—and transformed them into rolling works of art. Lowriders, with their candy-colored exteriors and slow cruising style. Were bold declarations of cultural pride, reviled by the mainstream and especially by the police. These cars became symbols of defiance, making an often-overlooked minority visible in the most unapologetic way possible.

In a similar vein, CASABLANCA’s collection glittered with denim paired with kaleidoscopic shirting. While jersey-inspired tops and surf gear hinted at a lifestyle of sun-soaked rebellion. Yet much of this iconography, steeped in Mexican-American history and American basketball swagger. Was likely lost on the European fashion audience and press. American buyers and media, more attuned to the subtleties of these cultural references, might have appreciated the homage more deeply. It’s easy to see how some fashion outlets, unaware of this backstory, might dismiss it as another Californian fantasy. Lumped together with the Grateful Dead and bohemian nostalgia.

Still, despite these potential misinterpretations, CASABLANCA did what it does best: go full throttle toward a bright, bold statement. It was more than just a collection. It was a reclamation of cultural narratives that have long been appropriated but seldom understood. Whether Paris will fully embrace it remains to be seen. For those in the know, the message was unmistakable: this was fashion with a voice, and it spoke volumes.

Share this post

Patrick Michael Hughes is a fashion and decorative arts historian. He writes about fashion culture past and present making connections to New York, London and Copenhagen's fashion weeks with an eye toward men's fashion. He joined IRK Magazine as a fashion men's editor during winter of 2017.

He is often cited as a historical source for numerous pieces appearing in the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, CNN, LVMH, Conde Nast, Highsnobiety and others. His fashion career includes years as a fashion reporter/producer of branded content for the New York local news in the hyper digital sector. Patrick's love of travel and terrain enabled him to becoming an experienced cross-country equestrian intensively riding in a number of locations in South America Scandinavia,The United Kingdom and Germany. However, he is not currently riding, but rather speaking internationally to designers, product development teams, marketing teams and ascending designers in the US, Europe and China.

Following his BA in the History of Art from Manhattanville College in Purchase, New York he later completed graduate studios in exhibition design in New York. it was with the nudge and a conversation in regard to a design assignment interviewing Richard Martin curator of the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art he was encouraged to consider shifting his focus to the decorative arts with a concentration in fashion history and curation.

Patrick completed graduate studies 17th and 18th century French Royal interiors and decoration and 18th century French fashion culture at Musée Les Arts Decoratifs-Musée de Louvre in Paris. Upon his return to New York along with other classes and independent studies in American fashion he earned his MA in the History of Decorative Arts and Design from the Parsons/Cooper Hewitt Design Museum program in New York. His final specialist focus was in 19th century English fashion and interiors with distinction in 20th century American fashion history and design.

Currently, he is an Associate Teaching Professor at Parsons School of Design leading fashion history lecture-studios within the School of Art and Design History and Theory,

Read Next