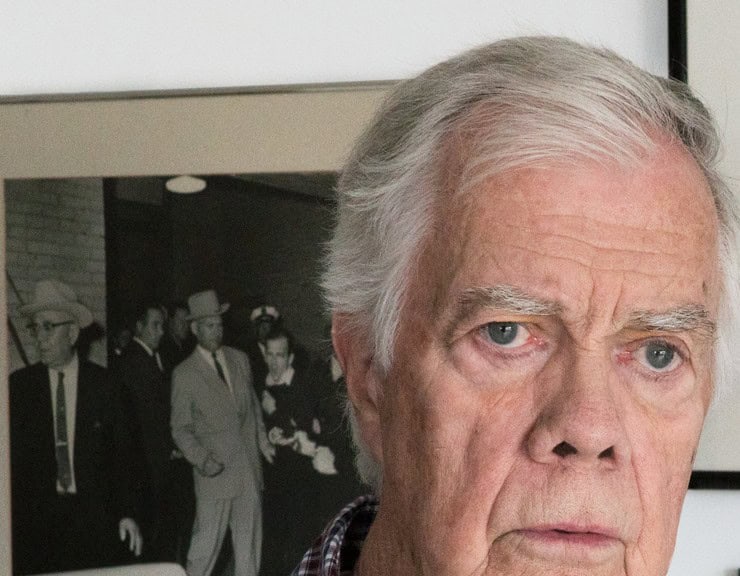

WITNESS // An interview with BOB JACKSON

Portrait of Bob Jackson, 2016 © Thomas Werner

There are few who have stood in the middle of history. Experiencing an instant that has defined a county, a world, or a people. Most do not choose to be party to these occasions, they are swept up in unknowing circumstances and brought to bear witness for the rest of us. The death of a President is one of those moments, as is the death of his assailant.

Bob Jackson was party to both of these events. One of four photographers riding in the Presidential motorcade. On the sunny November 1963, Dallas, Texas morning when President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed. Then again at the police station. When the gunman Lee Harvey Oswald was shot and killed by local club owner Jack Ruby. It was Jackson’s photograph of this later event that won the Pulitzer Prize for Photography that year. Placing Jackson and his era defining image in the center of a mythology that still surrounds a brilliant young President and his assassination.

Bob’s path to a Pulitzer began as a 12 year old taking pictures with a Kodak Baby Brownie Special. Though he can’t explain why it was so, he enjoyed taking pictures. By age 14 was asking his father to take him to Love Field to photograph the planes. Photography was an enduring hobby and his interest grew throughout high school, along with a new found passion for automobiles. A few years later his love for cars and photography led him to leave Southern Methodist University. As he was spending most of his time at Carroll Shelby’s Sports Cars. A business run by the legendary automobile designer and race car driver Carroll Shelby. Said Jackson, “When I stop and think about it, I really owe my career in photography to Shelby. Because I started photographing everything connected with racing and cars.” Yet Bob had to leave Shelby for a brief stint in the army. After which he had the good fortune to land a job as a staff photographer at the Dallas Times Herald.

It was the Times Herald that assigned Jackson to cover the arrival of John F Kennedy and his wife Jacqueline at Love Field Airport. Followed by a ride in the motorcade through downtown Dallas. Whichthat was to culminate with Kennedy’s speech at a noon luncheon. Bob photographed the President and First Lady as they got off the plane and walked over to the fence to greet the onlookers. After which they got into waiting cars for the drive to downtown Dallas. There were a few signs supporting Barry Goldwater, and Dallas did have a small group on the far right who did not like the Kennedy, but 99% of the people at the airport were excited to see the President that day. Jackson described the motorcade into the city. “The convertibles were driven by Texas Rangers, as far as I remember. There were four media-people in car, we were seven cars behind the President. Eight cars behind the lead car, which was unmarked police leading the procession.”

Bob’s assignment was to photograph as much as he could along the parade route. There was not much to shoot other than crowds of people lining the street. Many standing quite close to the cars. He noted, “We went through the downtown area, there were a lot of people. Up on balconies, hanging out of windows, but I had to unload the camera. We had a photographer downtown, so I wasn’t worried about not shooting what I saw. Unloaded the camera with the long lens, but did not unload the other one. I put the film in an envelope, and as we turned the corner (at Main and Houston Streets) tossed it to a reporter we had waiting for us. He missed it in the gusty wind and kind of had to kind of chase it. We were all laughing as we made the turn and then we heard the first shot. Then a pause, and then two more, closer together. The sound came from directly in front of me, so I looked up at the depository. There was a rifle resting on the ledge, and it was immediately was drawn in. Even if I had had film in the camera, I don’t think that I could have reacted fast enough, let up and focus. At least I told myself that, it makes me feel better, you know. But I said, “There’s a rifle.” And Tom Dillard, who is the Dallas News chief photographer, was sitting next to me up on the back of the seat, and he said “Where?”. I pointed to the empty window, and of course he took a picture of that.

In the confusion they were not sure who was the target or if anyone had been injured. Bob noted, “I had no idea who was hit, if anybody was hit. We stopped at the intersection before making a left-turn, waiting long enough for the other guys in the car to get out. So I look at the scene, and on the grassy-knoll there’s a couple covering their child. There are people running across the grass and in the street, there’s a motorcycle cop, he drives up the grassy-knoll, jumps off, doesn’t even shut the motorcycle off, it kept going, he gets off, and then it fell over. He goes to the door of the book-depository, and another cop meets him there, and they go in. I kind of wish I hadn’t seen that, but I thought, well, they know where the shots came from. They’re gonna catch this guy, or kill him, or whatever. He isn’t going to get out of the building, and certainly not for us to photograph. So I stayed in the car, we were going past the grassy-knoll, and I’m just seeing this confusion and had second thoughts. By then we were under the underpass and I asked the driver to stop and let me out. So I got out, ran back up to the grassy-knoll, and still I don’t even know whether I loaded the camera or not. If I had had half-a-brain at the time I would have just started photographing with the wide-lens, the people were visibly upset. But by then, I mean the minute I got up there, I found that he (President Kennedy) had been hit. That it was really bad, he had been shot.”

Earlier in the day the President’s team had talked about putting the bubble top on the car while at the airport. Kennedy said, “No, I want to be able to see the people, and the people see me.” The bubble-top was not bullet-proof. It would have deflected, who knows where the bullet would have gone if it had hit it. At the last minute decision was to keep the bubble-top in the trunk.” – Bob Jackson

Though he did not know where Kennedy had been taken Bob assumed it was Parkland Hospital. Along with other photographers began to look for a way to get there. “We just flagged down this woman in a red car. Asking her “Would you take us to Parkland Hospital?”, and she said yes. So we get up onto the entrance ramp to the freeway. There is a motorcycle cop standing there stopping traffic, checking everybody. We told him who we were and that we were on the way to Parkland. While we were talking his motorcycle radio is blaring away and I heard this guy say. “We don’t know where the shots came from.” So I said, “Oh, I know.”, and I told him I know where they came from, “that building”. I mean I wasn’t even sure what the name of the building was. He took my name and phone number and let us go.”

The next day, which was a Saturday, was Bob’s day off with Sunday his regular day to work. That Sunday morning he was assigned to the police station. To get a picture of Lee Harvey Oswald being transferred to the county jail. After which Bob was to go to Parkland Hospital where Nellie Connally (wife of the Governor) was going to give a press conference. Jackson arrived at the city jail at about 8:30am. As he entered he notice there was not any security at the door, nobody checking I.D’s, so he walked to the elevator and went up to wait in the pressroom. Eventually they took everyone down to the basement to cover the transfer. Oswald would be brought down the elevator to the booking room and then out the door to where prisoners were picked up or dropped off.

Pulitzer Prize winning photograph of Lee Harvey Oswald getting shot by Jack Ruby., November 24 1963 © Bob Jackson.

Time passed and the 9:30am transfer was not going to happen as planned. Bob asked a reporter for the Times Herald to go inside and call the newspaper to let them know what was happening. The young man on the city desk that day told the reporter. “You go back and tell Jackson, if he can’t get the picture of Oswald and make it to Parkland Hospital in time, he can just blow that assignment off, because we have Haymend (another photographer) down at the county jail, and he’ll get a picture of Oswald when they bring him in, because we can’t miss that press conference.” When the reporter returned Bob said, “You go back and tell him, I’m not leaving here, and he better find somebody else.” As it turned out a photographer from United Press International was going to be covering the press conference at Parkland Hospital, and for history’s sake Jackson was able stay at the city jail.

Just after 11am the press were told, “We’re bringing him down, you’ve got about five minutes to get in position, pick a spot, we don’t want anybody moving around, we want everybody still.” Jackson recalled, “I don’t think that there were more than 30 people in that basement, at the most. There were four still photographers, AP, UPI, Dallas News, and me. There was one pool TV camera, with lights and I think a couple of TV guys with handheld cameras.“ The police were going to take Oswald from the basement entrance of the building to an armored car waiting at the top of the ramp. The original plan was for the car to back directly up to the door of the building, but this was not possible as it did not clear the roof of the structure. This meant a change in logistics for everyone involved. The four photographers covering the transfer each took a different position along the building entrance and ramp, with Jackson standing directly in front of the door. Jack Beers from the Dallas News got up on the wall as he liked to shoot from above the crowd. Frank Johnson, a young photographer from UPI stood a few feet to Bob Jackson’s right, and the AP photographer positioned himself near the armored van in which Oswald was to be transferred.

This was a picture Jackson had taken many times, a prisoner being walked from the police station to a waiting car before being taken to jail, yet the gravity of the scene made this different. He described the moment Oswald emerged, “I saw him coming through the booking room and out the door. I’m looking through the camera, all of a sudden there’s a car moving next to me, an unmarked police car backing into place. I took a step to my right, because I didn’t want him to roll over my foot. As the car stopped, they walked into the clearing (Oswald and Jim Leavelle who was handcuffed to the prisoner), Jack Ruby stepped out and fired, and I shot the picture. I was looking through the camera the whole time, watching it, and I remember looking down and making sure the car wasn’t moving anymore, and it all came together. Well, after the shot, I wound the camera knowing full well that the strobe wouldn’t recycle fast enough, it just wasn’t going do it. After that, a cop jumps on the hood of the car and goes right up over the top of the car, down the trunk into the crowd to help. The next thing that I remember is a cop pushing me back with his hand, and his hand right over the camera, and I said, get your hand off my camera. And he was just livid, and another cop next to him said calm down, or quiet down, or they’re not going anywhere, don’t worry or whatever, quiet him down or something. And so, there we were, and of course they hustled both Ruby and Oswald into the building, and we just waited there until the ambulance came.” Jim Leavelle later recounted to Jackson his walk through the jail with Lee Oswald before emerging to meet the press. When they were in the booking room, Leavelle said, “Well, Lee, I hope if anybody tries to shoot you I hope that they’re as good a shot as you are.” Oswald replied, “Nobody’s going to try to shoot me.” Those were Lee Harvey Oswald’s last words.

The newspaper wanted to send a runner to get Jackson’s film and take it back to the newsroom to be developed, but Bob was not going to take a chance and headed back to the office with film in hand. Upon arriving he got off the elevator and saw a crowd of people around the wire machine. Said Jackson, “They called me over, and they were looking at Jack Beers shot, which was taken six-tenths of a second before mine, which you’ve seen, I’m sure, where Ruby’s pointing the gun, Oswald’s looking that way. So they said have you got anything as good as this? I said, I’ll let you know when I run my film…I remember holding the film up, wet, looking at it, and I wasn’t really worried about it being sharp because it was direct flash, but I was concerned about timing, you know did I shoot too soon, or did I shoot after the bullet entered the body? But I remember letting out a yell, because I knew I had something good. And so John and I made a wet print and carried it out to the newsroom, and then everybody was excited because we had beat our competition.”

Over the years Bob Jackson has stayed in touch with Jim Leavelle, the Dallas, Texas, homicide detective in the white suit and wide brimmed hat who was handcuffed to Lee Harvey Oswald when Jack Ruby fired his fatal shot. During the course of their conversations, as well as those with others, Jackson was convinced that Ruby was acting on his own behalf when he killed Oswald. Jack Ruby had an ongoing interest in the police, at times stopping in at the police station with sandwiches for the night-shift after his club closed at 2am. He was a regular at the station and knew all of the police and they knew him as well. A story related to Jackson by Leavelle sheds a little more light on Ruby’s mental state as it applied to the police. Jim told him that years before, when he and another officer were making their closing time rounds of some of the night-clubs in town, they walked into one establishment and saw Ruby sitting at the end of the bar. Leavelle spoke to Ruby who said, “I would like to help the police, I always imagine that something would happen to you and I would save one of you cops.” Said Jackson, “That was his mindset. He wanted to be, in a way he wanted to be like Oswald, he wanted to be recognized.“

When I asked Bob if Ruby carried a gun he replied, “Ruby Always had a gun, oh yeah. Oh yeah, and it was spur of the moment. Although he was upset, because he loved Kennedy, he closed his club. The next day, he was mourning, he really was. But he was also a guy who wanted to be a hero.”

Yet the question has always remained as to why Jack Ruby was at the city jail at the time Lee Harvey Oswald was being transferred. Bob explained that on the morning Oswald was shot. Ruby had received a phone call from one of his strippers living in Fort Worth, Texas. Saying she did not have enough money for her rent. Jack put his dachshund in the car and drove to the Western Union Office. Which was located at the other end of the block from the police station to send the funds. At 11:17am Ruby wired the woman $25, the time of the transfer was stamped on the wire. After sending the money Ruby walked down the street toward the entrance of the ramp at the jail where Oswald was being held. It is interesting to hear Bob describe the scene on the ramp that morning. “The police had decided they would take an unmarked car out the entrance ramp with two cops in it. It had to go around the block and get in front of the armored van and lead the parade. They get in the car, they can’t go out the exit of the ramp so go out the entrance. As they’re coming up the entrance ramp, Ruby is walking along the sidewalk. The cop standing there steps out into the street to make sure that any traffic (stops). Which on Sunday morning there was almost none. Whether he saw Ruby there, I don’t know, the car goes out, Ruby walks down, shoots him (Oswald). Now the time on this was under four minutes. Now you tell me he was sent there to execute him. We didn’t even know they were bringing him (Oswald) down, you know until (it happened).”

It is important to note that Lee Oswald was killed at 11: 21am, after questioning had delayed his transfer. That gave Jack Ruby less than 4 minutes from the time he sent the wire at 11:17 to walk to the police station and down the ramp before shooting Oswald. Why Ruby was let down the ramp we will never know, but his actions that morning changed history. The Jackson’s told us that after the shooting Jim Leavelle asked Jack Ruby, “Why did you do that?”, to which Ruby replied, “Well, I just wanted to be a hero, and I guess I really messed up, didn’t I?” Jim said, “Yeah, you did.”

Jackson was in the newsroom snack bar when he learned he had won the Pulitzer. Though it brought him fame, he decided to stay in Dallas covering the local news, later in his career in doing the same in Colorado. Some Pulitzer Prize winners work abroad, but this allowed him to create a more consistent life for himself and his family while continuing a career he loved.

Pulitzer Prize winning photographers are humble heroes, people who are for the most part without ego. Their lives are dedicated to bringing us the pictures that define our era. In the case of Bob Jackson, it is a photograph that signifies one of America’s turning points, an image and a time that are seared into our collective consciousness.

Written by: Thomas Werner, Editor at Large IRK Magazine, Assistant Professor at Parsons School for Design in New York. Author of the upcoming book The Fashion Image, due out in January 2018, Bloomsbury Publishing, London.

Instagram, Facebook @ThomasWernerProjects; Twitter, SnaptChat @TWprojects

Share this post

Thomas is the author of the books The Business of Fine Art Photography, Routledge, New York, and The Fashion Image for Bloomsbury Publishing, London. As a creative consultant, Thomas works one on one with students, creatives, businesses, cultural institutions, and not for profits helping them refine their communications, and achieve their goals in fashion and the fine arts. He is also an Editor at Large for IRK Magazine, a member of the Santa Fe Council for the CENTER for Photographic Art, an instructor at the New York Film Academy and Santa Fe Workshops, founder of Thomas Werner Projects Podcast, and past Photography Program Director at Parsons School of Design in New York. He is the former owner of Thomas Werner Gallery in Manhattan’s Chelsea Art District, and a former National Board member and New York Chapter President for the American Society of Media Photographers. As well as a former Advisory Board Member for Ithaca College’s Executive Education Program and contributor to Adobe’s Lightroom Academy. As an exhibiting artist Thomas was represented by galleries in New York and Los Angeles, and his work reviewed in The New Yorker Magazine.

Werner also led a team developing a media and literacy web site and resource center in five languages, Spanish, French, Russian, Arabic and English for the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations/UNESCO. He has worked with the United States Department of State on cultural projects in Russia, and been a photography consultant for COACH and Rodale Publishing, among others. Thomas was a recurrent instructor at the United Nations Education First Summer School, and is now presenting workshops on effective message development, team management, innovation, education, visual communication, contemporary professional practices, on an international basis. With a series of presentations and workshops in 6 cities across China.

From 2005 – 2020 his research was Russia centric spending an average of 30 days a year there partnering with 32 cultural, educational, and governmental organizations to develop projects in 29 cities. The focus has been the introduction of contemporary education methodologies, and the development of creative cultures within the country. Russian partners have included; The State Hermitage Museum, the National Center of Contemporary Art, Perm Regional Government, The Moscow Biennale for Young Art, National Centre of Photography for the Russian Federation, The Central State Archive of Film, Photographic and Phonographic Documents, The Moscow Biennale, The Pro Arte Foundation, and others. He has curated exhibitions in the United States and abroad, including seven co-curated exhibitions at the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia. His private collection of Russian photographs and artifacts have been exhibited internationally. Thomaswernerprojects.com @Thomaswernerprojects IG

Read Next